Philadelphia, PA

- Philadelphia's Historic District, also known as America's Most Historic Square Mile, unveils the captivating story of the nation's founding. But beyond the well-trodden paths of Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell, a lesser-known narrative emerges – one that delves into African Americans' challenges, triumphs, and contributions throughout history.

Philadelphia's Historic District: Uncovering the African American Narrative

Museums and Historic Sites

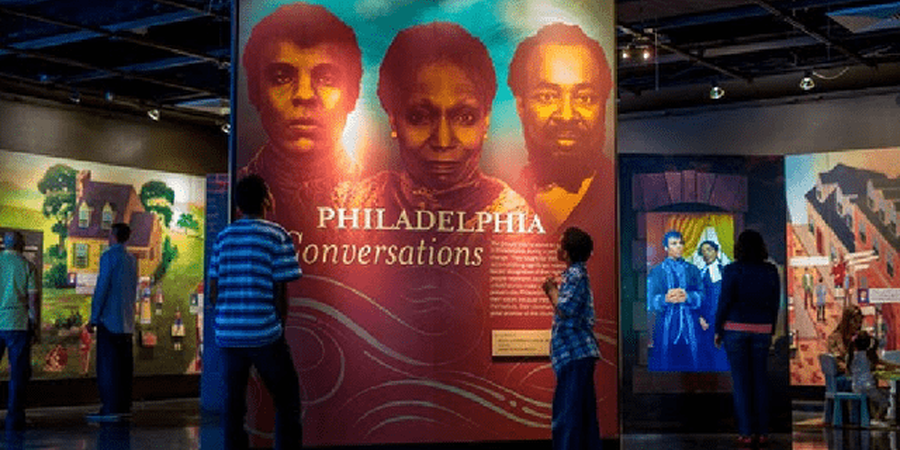

- The African American Museum in Philadelphia: Established in 1976 as the first major U.S. city-funded institution dedicated to African American history and culture, the museum offers a fresh perspective on their pivotal role in shaping the nation. Their core exhibit, "Audacious Freedom," along with other programs and displays, illuminate the diverse stories and experiences of the African diaspora.

- Independence Seaport Museum: The permanent exhibit "Tides of Freedom: African Presence on the Delaware River" utilizes the city's eastern waterway to reveal the profound impact of the African experience in Philadelphia. First-person accounts and historical artifacts chronicle 300 years of history, from enslavement and emancipation to the Jim Crow era and the Civil Rights movement.

- The Liberty Bell Center: Explore the Liberty Bell's connection to African American history. Interactive displays and videos shed light on how abolitionists embraced the bell as a symbol of freedom and how it toured the nation to promote unity after the Civil War.

- Museum of the American Revolution: Delve into the personal stories of African Americans during the Revolutionary War, including William Lee, George Washington's enslaved valet, and James Forten, a free Black man who volunteered as a pirate. The museum also features a signed volume of poems by Phillis Wheatley, the first published Black female poet in America.

- National Constitution Center: Through engaging exhibits and activities, the NCC highlights the contributions of notable African Americans and explores pivotal Supreme Court cases related to civil rights, such as Dred Scott v. Sanford and Brown v. Board of Education.

- National Liberty Museum: The museum's "Heroes From Around the World" gallery honors individuals who have championed freedom, including well-known figures like Nelson Mandela and everyday heroes like Gail Gibson, a New Orleans nurse who bravely saved lives during Hurricane Katrina.

- The President's House: This open-air site marks the location of Presidents Washington and Adams' residences. It serves as a poignant reminder of the nine enslaved Africans who lived and worked there, including Ona Judge, who courageously escaped to freedom.

- Washington Square: Once known as Congo Square, this historic park was a gathering place for free and enslaved Africans to celebrate their cultural traditions during holidays and fairs.

Churches and Sacred Spaces

- Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church: Founded in 1794 by Bishop Richard Allen, Mother Bethel AME Church stands on the oldest parcel of land continuously owned by African Americans. It serves as the mother church of the nation's first Black denomination and houses a museum with artifacts dating back to the 1600s.

- St. George's United Methodist Church: This church played a crucial role in the early African American Methodist movement, licensing Richard Allen and Absalom Jones as its first Black lay preachers. Despite a past marred by segregation, St. George's now actively works towards reconciliation and racial justice.

Historical Markers and Stories

Throughout the Historic District, historical markers tell the stories of influential figures, pivotal events, and important locations in African American history. These markers serve as reminders of the contributions and struggles of Black Philadelphians throughout the centuries.

Philadelphia's Historic District offers a multifaceted look at the nation's past, shedding light on the often-overlooked stories of African Americans. By exploring these sites, we gain a deeper understanding of their resilience, contributions, and the ongoing fight for equality.

Share This Article on Social Media